Welcome to the Introduction to R workshop. This week is to help total beginners set up and acclimate to R, while also providing a quick refresher to those that have previous experience with the language. This week has three distinct parts. First, there will be quick introduction about the history of the R programming language. There will also be a discussion of what R can do and what it can’t. Second, it will walk you through the necessary steps to install and use R and the popular IDE (integrated development environment) RStudio. Third, and finally, it will provide a quick introduction to the R programming language with a comparison to SPSS/Stata and an introduction to the logic of programming as a whole.

Obviously, if you already have previous experience using R, feel free to skip the beginning sections and focus on the refresher.

1. What is R?

For those without prior programming experience, or those new to statistical modeling and analysis, wrapping ones head around the concept of R can be somewhat daunting. So what is R? The correct, and somewhat ambiguous, answer is that it is a dialect of the S and S-PLUS programming languages. Before the golden age of powerful home desktops, the development of effective numerical processing took place almost exclusively within the auspices of established technology companies. A company that is relevant to our work here is the famous AT&T Bell Laboratories, the same research and development lab that created technologies such as the fax machine, the transistor, and even the first laser! Interestingly enough, they were also influential in the development of the C and C++ programming languages.

In 1976, a development team at Bell Labs under the direction of John Chambers1 developed the programming language S for the internal needs of the lab. It was made to streamline statistical analysis and was built from the famous FORTRAN programming library. Fast forward to the late 1980s, and S was redeveloped using the C programming language. This new version of S was very similar to the R language that we will be using in this workshop. During the 1990s the commercial and development rights for the S language passed hands to a variety of corporations. Eventually S-PLUS was developed as a commercial packaging of the S language that included a powerful GUI and a number of additional features. S-Plus is in many ways like other commercial packages such as SPSS, SAS, and Stata, yet was incredibly expensive to license. As an alternative to the S-PLUS system, two statisticians named Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman developed the R programming language. By 1995 the R programming language was officially released to the public under the GNU (General Public License). This made R a free software, which allowed for the entire R system, including the source code, to be freely manipulated by the general public.2

So we know a little bit about the history of R, but how does this answer the question of “What is R?” As stated before, R is a dialect of S and S-PLUS. R has a programming language syntax built specifically for the statistical analysis of data. As a result, it has conventions that are typically outside the norm for more general purpose programming languages. R is additionally free. Free to own and free to change. This openness has contributed to the development of large statistical programming community. The number of specific methods grows each year as individuals and teams contribute to the R package library. Additionally, R has guaranteed core updates that take place every few months.

Like any tool at a researcher’s disposal, R does have limitations. The core R syntax deviates from modern user friendly programming concepts. This is partly because R is based on a language that dates back nearly fifty years. R additionally requires the user to keep objects in physical memory, which can be taxing on low to mid-range computers. Finally, methods and packages are almost entirely user developed and based on internal need or a certain threshold of external demand. If you happen to need a highly specialized method that no one else has used in fifteen years, odds are that you may need to program it on your own, hire someone to program it, or wait for someone else to do so.

This has been an overly brief introduction to the history and concept of R. We will focus more on the application an use of R than its history and the theory behind why the language works, but it is important to know something about the program that you are using. To many R is a puzzle that needs solving with a lot of hard work. This is not to say that learning R won’t be challenging (it will), but there is value in humanizing such a daunting program. Remember that many people struggled and fought to create the powerful system you will begin to use, and many more struggle to learn and adopt it today. You are never alone, and with curiosity and patience, you will come to use R as fluidly as any other tool at your disposal.

2. Installation and RStudio

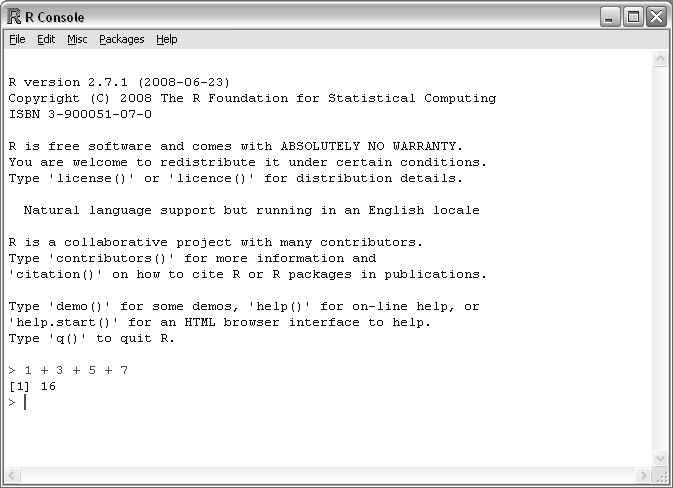

R is compatible with Windows, OSX, and Linux systems and is easy to install and get running. The core R files, and packages, are housed on CRAN (Comprehensive R Archive Network, https://cran.r-project.org/index.html). Following the link to the CRAN page will show you links to your specific system’s version of R. It is advised that you download and install the base R package onto your main hard disk. The installation for Windows and OSX come in the form of an executable, and should be easily installed like any other program.3 If all goes according to plan, you should be able to open R from your list of applications. You will see a small minimalist box that will look similar to the picture below.

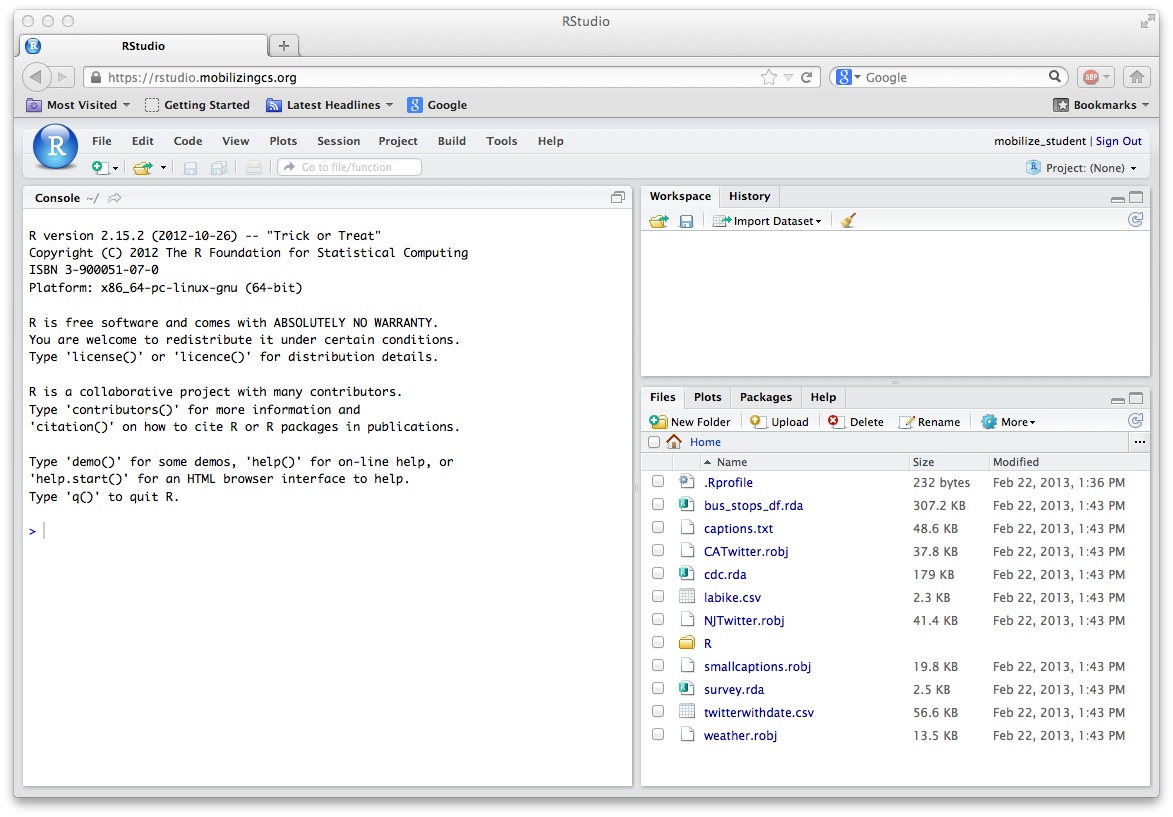

Usually, this would be the part that you are introduced to working with the R console, but we are going to skip that for now. For the purposes of this workshop we will utilize RStudio as a tool for streamlining the use of R and project creation. RStudio (https://www.rstudio.com/) allows you to more easily house data, code, and graphical results in research project folders and helps you to consolidate your package library across projects. Download the desktop version of RStudio and follow the installation instructions. If all goes according to plan, you should be able to open up RStudio and see something that looks like the image below.

If you are having issues installing RStudio, check out the video by Roger Peng below:

3. Introduction to R programming and basic operations

This section serves as introduction to using R and also as a refresher of R programming concepts. It will first go over input and evaluation, second it will discuss the logic of objects and object types.

3.1 Basic Input and Evaluation

The easiest way to input commands into R is to utilize the console at the bottom left of RStudio. Try typing in 2 + 2:

2 + 2## [1] 4You should see a 4 display in the console. Try any variety of simple mathematical operations and take note of the results. In the end, R is basically a fancy calculator that can evaluate incredibly simple, or complex, commands. The command you typed above is stand-alone in nature, but you perform the same operation in a different way. Try typing the following command:

x <- 2 + 2What happened here, and why is it different? If you are using RStudio, you should see a x appear in the global environment tab. You will see that this x object has an internal value of 4. You have essentially taken the addition operation you previously specified and housed it in what is called an object. You may of noticed the <- symbol in this example, this is called the assignment operator. The assignment operator is important for the discussion concerning objects later in this lab. Now try typing the following two lines of code:

x## [1] 4print(x)## [1] 4Both lines of code have produced the same output, 4, yet they do it in different ways. Before going into detail about why, lets turn our attention to the idea of “objects”.

3.2 Vector Objects and Classes

The code you typed above demonstrates one of the most basic examples of an object in R. Objects house data as a sort of distinct physical entity that can be called upon in your R code. Objects can house almost anything and everything, but let’s start with the basics.

Vectors

Vectors are the most basic objects available to you in R. Look back at the code you typed in section 3.1, and the assignment operator. You used the assignment operator (<-) to create a vector object called x. The value of this vector is 4. Let’s demonstrate vectors again by typing the code below:

x <- 10:30What happened? You should see that the value of your x object has changed in the global environment. Here we simply created a vector of numbers that spans from 10 to 30. Try printing this object by using the code shown above:

x## [1] 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30You have printed a vector of numbers! The style of printing above is called auto-print, which is simply typing the name of the vector object. Try the other code that says print(x), and you will get the same result. The print(x) command is called explicit printing and occurs when you call the print() function. Don’t worry too much about understanding the difference for now, as we will go more in-depth on functions next week.

There are some conceptual issues that need to be discussed here. You are probably wondering where the previous x vector object went (x <- 2 + 2). One must be careful in naming conventions in R, especially when it comes to objects. If you use the same object name, it will overwrite the previously stored object. In addition to this convention, the basic vector object has an important rule that must always be followed, and that is uniformity of object class…

So what is an object class? Classes represent the specific type of data that can be housed in a vector. There are five distinct classes that are of importance to you at this point.4

- integer

- numeric

- character

- complex

- logical (Boolean)

Object Classes

Of these five class types, three are of most importance to you as a data analyst. These are numeric, character, and logical. The numeric class is straightforward, as it corresponds to any numerical piece of data. Our x object is a numerical vector for example. Let’s practice making a numerical vector again by typing the code below:

y <- c(1, 10, 500)Now we have two numeric vector objects in our global environment, but there was something different about this line of code. This time we used a function c() to create the vector. This function is called the concatenate function (don’t worry too much about functions right now!) to put three different numbers into a vector. The concatenate function is useful for creating any type of vector. Let’s try creating a character vector by typing the code below:

numbers <- c("one", "two", "three")You should see a new object appear in the global environment. Go ahead and print it using whatever form you wish.

numbers## [1] "one" "two" "three"The result of the print shows the words of three numbers! Take note of the quotation marks around the words. For character classes, also known as strings, you must specify it so by adding quotation marks around the word that you place into the character vector.

The final object class of interest here is the logical class. Logical, also known as Boolean, is a TRUE/FALSE representation of data. Without going too much into the logic behind logical classes of vectors, lets first go ahead and create one and print its contents.

logical <- c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, TRUE)

logical## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUElogical2 <- c(T, T, F, F, T, F, T, F)

logical2## [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSEThe result of the logical vector print shows the same pattern of TRUE and FALSE as our object. Notice that we didn’t have to use quotation marks for create this vector. In R, logical data as represented by TRUE and FALSE (T and F) forms its own distinct type that is separate from character strings.

Extra Credit

Try typing !logical or !logical2 into the console. What do you see? What do you think happened?

Back to Vectors

Let’s return to how classes fit into vectors. Each of the three classes you created above are vectors in of themselves, but what does the rule of uniformity have to do with any of this? The rule of uniformity is simple, it means that while you can create vectors with a variety of different object classes, you cannot create a vector with multiple class types. For example, you can’t create a vector with both numerical and character class types in the same vector. Let’s demonstrate this point.

x <- c(1, 2, 3, "four")

x## [1] "1" "2" "3" "four"While you were able to make a vector, notice that it has turned into a character vector! This is because R has decided to force a vector class of one type onto the newly created object, this is called coercion. You wouldn’t be able to use this object in any numerical operations as a result. Try adding 5 to the vector values of your new x character vector.

x + 5## Error in x + 5: non-numeric argument to binary operatorIf you want to specify the type of coercion that happens in the creation of a vector you can use the as.() function. Lets recreate our vector object of numbers that span from 10 to 30..

x <- 10:30Looking back at the newly created x object, it is clear that I somewhat mislead you concerning its object class type. Creating vectors this way (10:30) results in a vector of the class integer. Integers are similar to numeric classes in that they represent numbers, albeit in a different way (their differences are beyond the scope of this lesson). Since we want this vector to be numerical, we can coerce it to be so by using the above mentioned as.() function.

as.numeric(x)## [1] 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30This results in a display of x as a numeric vector, but we can also change x to become a numeric vector by using the as.() function.

x <- as.numeric(x)You are probably already guessing that the as.() function can take on any class need. Here is a convenient list of as.() function types you can use for the classes discussed so far.

- as.numeric()

- as.logical()

- as.character()

Try quickly coercing your x object into logical and character types.

-

John Chambers is a statistician and computer scientist at Stanford University. His efforts laid the foundation for the widespread adoption of R within the statistics and scientific community. ↩

-

For a more detailed treatment concerning the exciting history of R, see R Programming for Data Science (2015) by Roger Peng. ↩

-

As I do not own a Mac, I am less familiar with issues concerning OSX installation. If you run into any trouble, consult http://www.r-bloggers.com/installing-r-on-os-x/. Google may also be your friend. ↩

-

There is a sixth object class called raw, but this is of near unimportance in the typical statistical analysis framework. ↩